“The New Colossus” Will Put the Focus on Refugees: One Local Business Leader Shares His Own Family’s Harrowing Experience and How It Has Inspired Him to Help Other New Arrivals

Bank of America executive and former Blumenthal Performing Arts Trustee Riaz Bhamani might not be alive today if his family hadn’t gotten out of Uganda when it did. In the early 1970s, his father was a prominent businessman, running the largest tea and coffee import-export brokerage in Uganda when the brutal dictator Idi Amin came to power through a military coup.

(Riaz Bhamani celebrating a birthday with his brother and father in Uganda)

Although Bhamani’s father was born and raised in Africa, his grandparents had originally emigrated there from India. As part of Amin’s reign of terror, he began targeting people perceived as threats to his regime—including Asians, whom he officially expelled from Uganda in 1972, giving them 90 days to relocate.

“I have memories of being in Uganda when the military would come to your house, force everyone to sit on the floor and they would ransack your house to take any valuables that you had,” Bhamani says.“That happened all the time so you never kept valuables, you kept them all at the bank.”

While his family knew they would have to leave, they believed they had time to plan their departure because of their financial means and business connections. Bhamani’s father busied himself helping others in the community. As the Treasurer of the local Mosque, it became his responsibility to help those with the greatest need to relocate to other countries and resettle. He also assisted various families in moving their possessions and assets with them, something that was not permitted under the new law. When some of this work came to the attention of the government, a warrant was issued for his arrest.

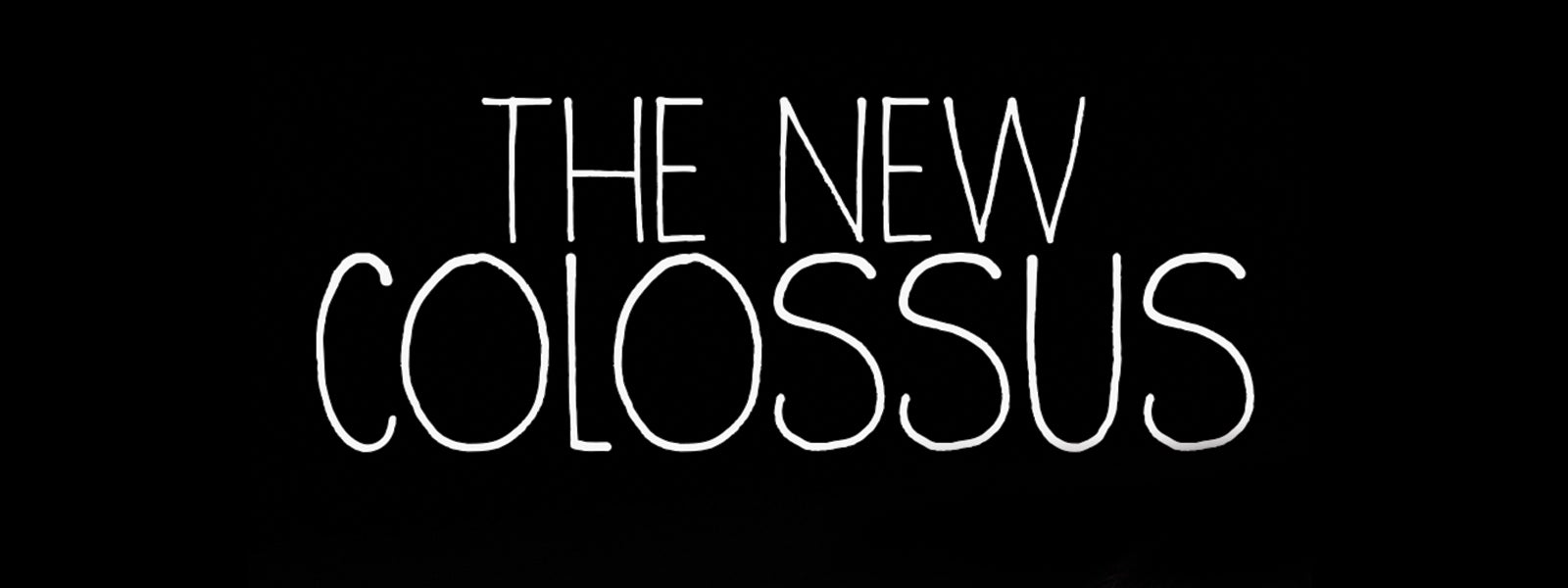

(Riaz Bhamani's mother and father)

Suddenly, everything changed.

“In Uganda, at that time, when a warrant was issued for your arrest, you disappeared,” says Bhamani, noting that a warrant almost certainly led to torture or execution since no real trials existed. (Under Amin’s eight years in power, it is estimated as many as 300,000 people were murdered.)

A HASTY DEPARTURE

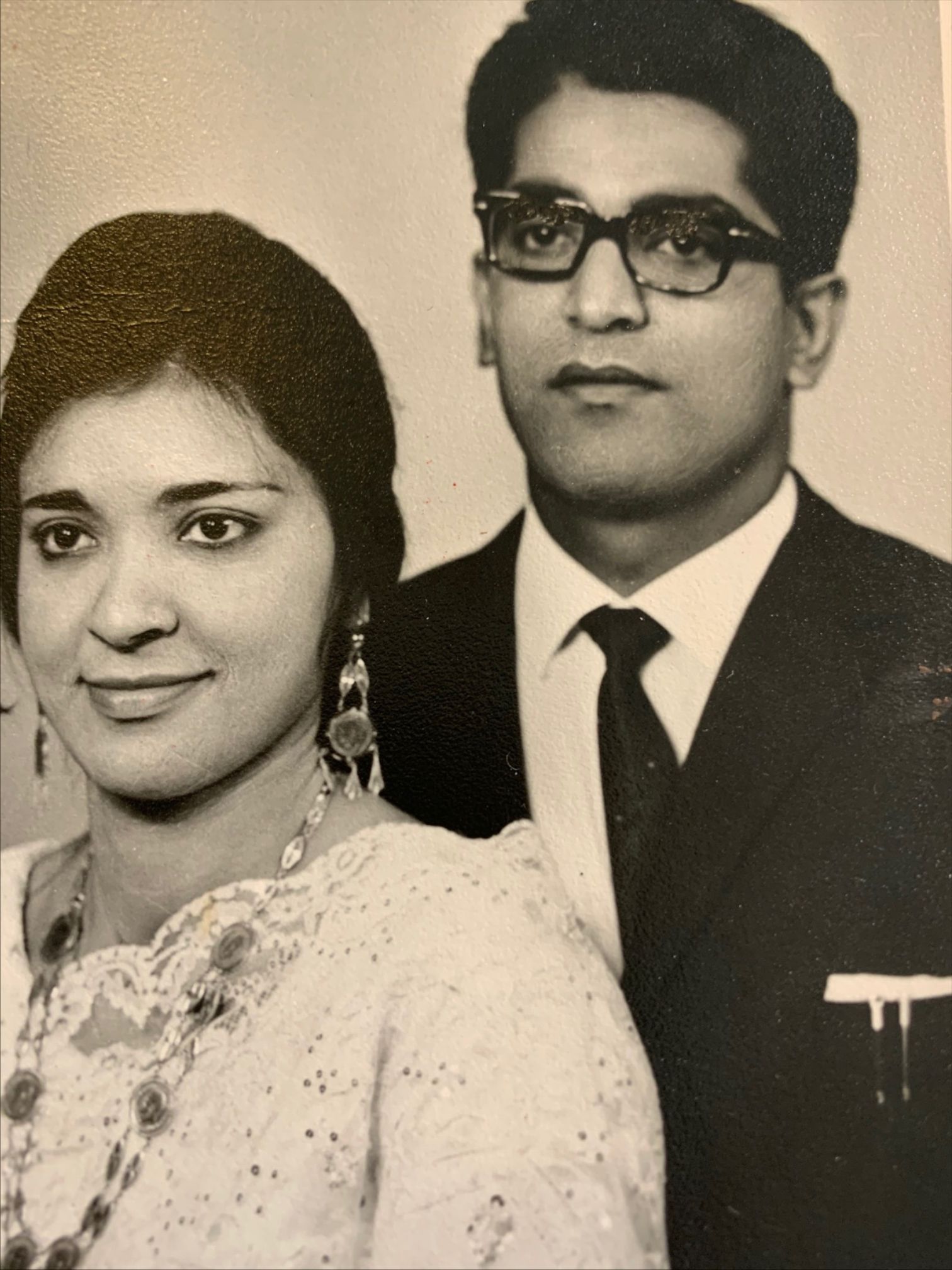

Bhamani, who was only four years old at the time, remembers his father coming home and telling them it was time to go. His mother packed whatever she could and within about 90 minutes, they were at the airport, purchasing plane tickets. His mother, a native Kenyan, had documents stating she was from the Commonwealth. But his father had to alter his paperwork, dropping the family name he’d always used per local tradition to identify himself with his true last name, Bhamani, which almost no one knew.

(Riaz Bhamani being held by his mother in Uganda)

He scratched off "Rashid" from the thick paper, told his two young boys to forget that name, and his wife, a teacher who knew how to write in the calligraphy then used on official documents, wrote in "Bhamani." That's been their last name ever since.

Once their flight arrived in the UK, the family applied for asylum. It was granted and after living in refugee camps for several months, the family eventually was resettled in Canada. A nurse they had met in the UK, who cared for Bhamanis brother when he fell ill, had taken interest in the family’s story. She had a brother who worked at Lipton tea in Canada and through that connection helped find work for Bhamini’s father as an Accounts Payable Clerk. That transition from one cultural landscape to another, learning to navigate in this totally different place deeply marked Bhamani’s childhood.

EXPLORING THE REFUGEE EXPERIENCE THROUGH THEATER

It’s this kind of journey—of refugees and immigrants—that will be featured in the upcoming play, The New Colossus, coming to Knight Theater, Jan. 28 - Feb. 2. In this innovative new work, created by Tim Robbins and The Actors’ Gang, 12 actors share 12 diverse stories in 12 languages from different eras inspired by their own ancestors’ experiences fleeing their homelands for a new life in America. The New Colossus, which debuted in early 2018 in Los Angeles, will kick off its national tour in Charlotte, in a production that also uses music, poetry and movement to tell these gripping stories.

“Save for the Native Americans, all of our families came here as refugees, immigrants or slaves,” writes Academy Award-winning Robbins about the production he co-created and directs. “The characters in the piece all seem different, from different parts of the world, traveling at different times—but the stories are remarkably the same: the common experience of all refugees is that they are fleeing some kind of oppression and moving toward safety and hopefully, freedom. Our hope is that we will be able to illuminate the courage, fortitude and humor of all refugees, and, perhaps, our own families.”

LEARNING A NEW WAY OF LIFE THROUGH TRIAL AND ERROR

Bhamani says he’ll undoubtedly use his own family as a reference point (as others in the audience will surely do with their personal histories) while watching these stories unfold on stage. For him, it will likely bring back memories of those early days as a refugee, how everything was different from what he and his family had known before.

(Aerial view of the Ugandan city the Bhamani's once lived in)

Miscommunication and having no one to turn to while decoding a new way of life were at the root of most challenges they encountered early on.

For instance, Bhamani’s parents wanted him and his brother to get the best education possible, so they took every opportunity they could find. “My brother and I were in Sunday School for probably about four or five months before my parents understood that Sunday School was about Jesus and the Bible,” says Bhamani. “They thought I was learning reading, writing, arithmetic. And for a family who grew up as orthodox Muslim, going to Bible study on Sundays was not what you wanted your kids to do.”

Food was also different. Bhamani knew chili as the hot peppers his mother used to make traditional Indian dishes. Imagine his surprise when a friend told him he was eating chili for dinner. “I couldn’t fathom how somebody could eat a bowl of cayenne pepper for dinner and I felt so out of place,” Bhamani says. “I felt like, ‘why don’t I understand it?’”

Social rules and expectations differed too. His parents, who had known life in close-knit village communities, had grown up in a culture with a different concept of the responsibilities and amount of trust appropriate for a child.

“I think I was five or six when my parents got in trouble because somebody found out that I was allowed to come home by myself and that I had a key to the house… and they were like, ‘you can’t do that!’ and they were like, ‘Why?’”

Over time they made connections and bonded with others in the refugee community and built a new life. As a teen and young adult, Bhamani says he rebelled a bit, moving away from home, not wanting to follow in the traditional path his parents had envisioned for him. Now, in hindsight he has a new level of appreciation for the sacrifices they made.

(Riaz Bhamani, his mother and two brothers at a grandparent's burial site, during a recent trip back to Uganda)

“When I was a child, I didn’t get it. I didn’t understand how hard it was for them. I didn't understand that they had left behind everything that they had. They left behind, not only the material things but every dream, every idea of what their family would become, of what their children would become, what their old age would become. Those were all gone and they had to come here and start all over again.”

HELPING NEW REFUGEES GET ACCLIMATED TO CHARLOTTE

This new understanding of his parents’ struggles and how difficult it can be for refugees to acclimate to a new place and culture prompted Bhamani and his family to get involved with the local non-profit Refugee Support Services (RSS). Bhamani now serves as Vice-Chair of the organization’s Board of Directors. RSS helps refugees navigate their way in the Charlotte community, assisting with everything from renting an apartment and job seeking advice to helping locate doctors who speak a refugee’s native language, providing tax or legal advice, enrolling kids in school or providing tutoring help. They host fun events to help refugees build connections, provide fresh food distribution to supplement what they may be able to afford, and pair refugee families with local families who can offer friendship and advice.

“When you understand what somebody has gone through, you have a brand new level of respect,” Bhamani says. “No one ever complains about it. Every refugee I’ve ever worked with—none of them have ever complained about anything they left behind. All they want to do is rebuild and be successful where they are.”

The organization’s motto is: Arrive, Survive, Thrive. Bhamani says when refugees come to Charlotte, they are given a place to live for three months and $1,000 and told to make their way in the world. RSS helps these new immigrants with their immediate needs but also sets them on a path to becoming contributing citizens in our community. Approximately 17,000 refugees have been resettled in Charlotte since the 1990s.

“To the extent that I can contribute to them becoming successful, I want to make sure I do that,” Bhamani says. “I think that I have been very, very lucky in my life. From where my parents started... to the opportunities that I’ve had, the doors that have been opened for me [have] led me to be able to provide all kinds of things for my children. I want to make sure I’m one of those people helping someone else provide the things that they really want to give their kids.”

WANT TO GET INVOLVED?

Visit refugeesupportservices.com or drop by the Galilee Center at 3601 Central Avenue for more information on volunteering or donating. You can also help by supporting RSS’s signature fundraising event, Laughter Without Borders, at The Comedy Zone on Feb. 11.